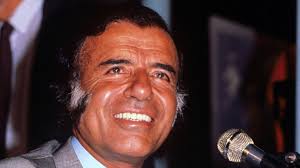

È morto, all’età di 90 anni, l’ex presidente argentino Carlos Menem, che governò il paese tra il 1989 ed il 1999. Menem, peronista, ereditò un’Argentina in piena crisi economica. E dopo averla salvata dal mostro dell’iperinflazione seguendo politiche neoliberali che erano agli antipodi delle sue promesse elettorali, in piena crisi la lasciò – sempre grazie a quelle politiche – dopo un decennio di governo (o, per una buona parte, di malgoverno). Quelli di Menem è il classico ritratto in chiaroscuro, laddove lo scuro, tuttavia, nettamente prevale sul chiaro. Ecco una serie di articoli a lui dedicati selezionati da Latin American News

Carlos Menem, who died at the age of 90 on February 14, 2021, was president of Argentina from 1989 to 1999. Having been in frail health for some time, he died after a short hospitalization for a urinary tract infection. Despite his Peronista origins, he became known for market economic policies and the privatization of state-owned enterprises. Under Menem, Argentina shifted toward a free-market model that was favored by international investors. Yet, beyond his obvious accomplishment of reigning in Argentina’s hyperinflation, which made him very popular with Argentine voters, the Menem years also saw growing unemployment, economic inequality, and expanding foreign debt. At the time of his death, he was still a sitting senator for the Province of La Rioja. Commentators around the region wrestled with his whirling legacy.

Menem’s Obits

El Universal of Mexico City reported that Menem’s body would be buried in the Islamic cemetery of the province of Buenos Aires, where the remains of his eldest son, Carlos Menem Jr, rest, despite the fact that Menem converted to Catholicism.

MercoPress of Montevideo wrote that “Ex-president Carlos Menem, political wizard and bon vivant, dies aged 90.” “Menem was considered a lover of fast cars and beautiful women. He relished the company of celebrities, hosting the Rolling Stones and Madonna in Buenos Aires.” Menem “ruled Argentina during a time of short-lived economic stability, and he enjoyed an often flamboyant lifestyle.” “A criminal lawyer by training, Menem was also supremely flexible as a politician, beginning his career as a self-styled disciple of General Juan Domingo Perón, who founded Argentina’s populist movement that bears his name and placed the economy largely under state control. But in Menem’s two terms as president, he transformed the country but in the opposite direction.” His parents were Syrian Sunnite immigrants, who arrived in Argentina in 1920 and owned a winery and olive groves. “Menem was a folksy, three-time governor of the poor northwestern La Rioja Province. Following in the steps of northern Argentina caudillo, he was noted for shoulder-length hair and mutton-chop sideburns when he came to international prominence.” He won the Peronist Party nomination and surged to victory in 1989 presidential elections, capitalizing on economic and social chaos in Argentina. The country at the time was mired in 5,000% annual inflation, “and the poor were looting supermarkets for food.”

Rodrigo Orihuela wrote in the Buenos Aires Times that President Alberto Fernández decreed three days of national mourning in the country and expressed “deep regret” at the former president’s death. Menem was “elected in democracy” and “persecuted and jailed during dictatorship,” Fernández added in a tweet. Ramón Puerta, who served as governor of Misiones Province during Menem’s presidential years, said in an interview in November 2016, “People remember the fight against hyperinflation, but Menem also found a country suffering large power shortages and put an end to them, and then made the country into a large exporter of oil.” Menem’s contemporaries credited him “for his creative style.” “Menem was a Pelé, a Maradona. He knew how to play with his feet, his head, his arms, with everything,” ex-Brazilian President Fernando Henrique Cardoso said in an interview in November 2020, comparing the Argentine with football’s top stars. BAT noted that “Menem left a legacy of grandiose announcements and controversial statements, including his 1996 promise to build a rocket ship that would carry people from Argentina to Japan through the stratosphere in 90 minutes.”

CartaCapital Magazine of Brazil noted President Fernández’s acknowledgement that, despite his neoliberalism, Menem was a strong defender of democracy. “When the dictatorship came, he was imprisoned for years.” Menem was elected as governor of La Rioja on two occasions, the first in 1973. He was removed from office at the time of the 1976 coup, and jailed for two years.

Sylvia Columbus wrote in Folha de S. Paulo that Menem’s presidency was marked by allegations of corruption. One of them was the arms export scandal to Ecuador and Croatia between 1991 and 1996, which would have generated transfers of about US$10 million for accounts in Switzerland. In 2013, due to the episode, he was sentenced to seven years in prison. The same happened two years later, when he was again convicted in another case, of bribery to authorities with public money. “All in all, the sentences tallied up to nine years of prison time, but he did not serve them, since the office of senator gave him parliamentary immunity.”

El Tiempo of Bogotá noted that the Supreme Court ended by acquitting him in 2018, after an appeal, considering that the “reasonable period of time” had expired for the carrying out of the sentence.

Federico Rivas Molina wrote in O Globo of Rio de Janeiro that “Argentinians remember Menem with devotion or contempt, as the father of a great transformation led with a statesman’s stature, or as an administrator of a catastrophe. Those who defend him remember the years without inflation, investment in infrastructure, and modernization of public services through privatization.” What is more, with the peso pegged to the dollar, well-heeled Argentines became first-class tourists, while imported products flooded the market. During his administration, Menem privatized, ceded, or dissolved 66 state-owned companies. “The sale of ‘grandma’s jewels,’ plus external debt flooded the market with dollars. Corruption was the hallmark of the times.”

Taking the Measure of the Man and his Legacy Across the Political Spectrum

Menem’s role in the rise of Neoliberalism in Latin America was clear, yet many pundits struggled to recognize his complicated trajectory.

El Espectador of Bogotá noted that his privatization efforts and liberal ideas “made him the pampered child of the International Monetary Fund, Wall Street investors, Republicans in the United States, and the Davos business forum.” Yet, he was also the last leader of a fully unified Peronismo, a political movement founded by Juan Domingo Perón in the 1940s that pulled together adherents reflecting ideological currents ranging from the radical left to the far right.

Luis Bruschtein wrote in Página/12 of Buenos Aires of “the man who was born for one thing but did the opposite.” Menem, the Peronista, “did what even military governments had not been able to do…dismantling what was still standing from the first Peronist governments: privatized all water, gas, and electricity services, communications, blast furnaces and steel, railways, airlines, and deregulated the economy. He did what not even the most neoliberal governments of the world had done: privatized the state oil company YPF.” “He represented in Argentina the clearest expression of the world wave of neoliberal globalization that proclaimed the ‘end of ideologies,’ a phrase meant that neoliberalism was not an ideology, but rather, expressed the natural and logical forces of the economy.”

In La República of Lima, Adolfo Cuicas pointed to Menem’s central place in the “era when Latin America embraced neoliberalism, driven by the failure and subsequent dissolution of the Soviet Union.” Some 30 years later, the picture is different with the resurgence of the left, though according to María Esperanza Casullo, neoliberalism “did not disappear in the region,” and many important actors still “defend certain orientations that we might call neoliberal, such as the need to shrink the state, to privatize public enterprises, regulate all trade transactions based on market mechanisms.” Menem privatized most public enterprises amid a major trade opening that brought Argentina closer to the United States, while also taming inflation in 1991. And according to Carlos Figueroa, neoliberalism “is not only a way to organize the market and the state,” it is also “a culture that strongly permeates” many political establishments in Latin America. “Countries such as Chile, Colombia, and Peru still have completely neoliberal policies in many economic sectors.”

Yet Menem’s story is complex. In El Mostrador of Santiago, Gilberto Aranda B. wrote of the “claroscuro tango” of Menem’s many political personas. Certainly, “Menem devoted himself to reducing the reach of the state and fragmenting the internal clusters of Peronismo.” Yet he was also a master interpreter of “pop politics,” understanding the need for a good “show,” “gradually replacing the balconies of the classic populists for cameras and the TV set.” Aranda noted that “Menem is often labeled as an icon of the predatory neoliberalism of the late 20th century, which, despite being true, requires a more nuanced view to understand the hybrid political type of this controversial character.” Menem, “belonging to the Peronista pluriverse, is not easy to place in the right-left spectrum.” Peronismo had many factions and leanings, while Menem “himself had more than one face.”

Fernando Fuentes wrote in La Tercera of Santiago that Menem became “the symbol of neoliberal Argentina of the 1990s,” and tried to impart the confusing nature of that time. During Menem’s administrations, “Argentina was transformed in full. Leaving aside the populist messages of his election campaign, he implemented an extraordinarily tough adjustment program, whose ultra-liberal character provoked attacks by organized labor and accusations of treason by many Peronists.” He pardoned military leaders and ingratiated himself to the United States and the United Kingdom (becoming the first Argentine president to visit London since the Falklands War). Yet his economic measures achieved economic stability without significant inflation, allowing for his reelection with 49.6% of the vote.

Mario Wainfeld argued in Página/12 of Buenos Aires that Menem was “a popular Leader, [with] an anti-popular legacy,” yet “at times he looked like a cat with seven lives,” (as they say in Spanish-speaking countries). While “privatizations were certainly in vogue in our region,” Menem “took them to the extreme,” beyond the actions of even Brazil and Chile, and did it brutally, bending workers’ rights. Yet the economic stability he brought, having stopped hyperinflation, “earned him long popularity.” Wainfeld noted that “hyperinflation overwhelms ordinary people, so economic peace was popular.” His reform of the Constitution in 1994 with former President Raúl Alfonsín to allow presidential reelection “proved beneficial to Argentines,” and allowed the rise of left-leaning Peronista Néstor Kirchner in the presidency. He pardoned dirty warriors, but was willing to smash a military uprising with considerable bloodshed, protecting democracy. He also “suspended compulsory military service,” which was much hated. Wainfeld “confessed” that “it’s hard to make a synthesis.”

Andrés Malamud wrote in La Nación of Buenos Aires of Menem’s “passion, impunity, and excess.” “Today it’s time to remember our Nixon, just as pragmatic, but warmer than the American: a fabulous seducer, or rather, a fabler.” He sold Argentines “a first-world tour as if it were a one-way ticket.” Like Nixon, “who pulled the military out of the Vietnamese swamp, Menem pulled the military out of the political swamp.” Yet, “the pardon with which he inaugurated his government was as immoral as it was effective: by releasing the criminals, Menem gained legitimacy to suppress them.” “I pardoned them, but I shot them,” journalist Martín Rodríguez offered as an appropriate epitaph.

Peronliberista mi pare una brillante definizione per il presidente che rappresenta la fusione di due malattie croniche tipicamente argentine: il peronismo e il liberismo. Che riposi in pace.

A me piace di piu liberonista, perche in realta Menem fu piu liberista che peronista.